Hi there! Jenn here. So, I’m having a really busy week – Elizabeth is crashing at my apartment tonight in preparation for our Busch Gardens trip on Friday, and I’ve been frantically cleaning between runs and ballet classes and work. And my room is still going to look terrible. Hopefully she won’t actually see it. Elizabeth, if you’re reading this, I hope you don’t see my room. It’s a mess.

Where was I? Oh, yes. Busy. Therefore a lack of posts. But lack of content makes me anxious, so may I offer you something I wrote a LONG time ago? As in 2009? For grad school? As my cultural policy final paper?

Wait, come back! It’s about Epcot! Cultural policy as displayed in World Showcase, with cameo quotes from books like David Koenig’s Realityland and that massive Disney biography. It’s long, but maybe it’s kind of interesting? Possibly? As I said, it was written in 2009 and much has changed since then, but… well… anyway…

All sorts of cultural intersections exist within the Disney universe. From cartoons to movies to theme parks, numerous unofficial foreign relations have been umbrella-ed under the Disney name. It is in the moving pictures that Walt Disney made his first mark, but, being a fickle creature and easily bored, his attentions soon turned to a project he called Disneyland, and later Walt Disney World.

Though conceived as a place for families to have fun together, it was and is an inadvertent introduction to world cultures, especially for children who have little or no previous experience. In so innocent a context as Disney, this fact should be harmless, unremarkable. Yet many find the implications dismaying. “Millions of Americans,” comments Kurin as quoted in James Bau Graves’ Cultural Democracy, “learn about world cultures through Disneyland and Disneyworld [sic] where they see the pirate-like people of the Caribbean drinking, and pygmies of Africa rising out of the river to aim their spears at your body—with knives and forks presumably to follow. Only slightly less dismaying is Disney’s ‘’It’s a Small World, After All,’ a tableaux of cute, little, formulaically but differently costumed doll figures meant to represent all the world’s people singing the same song—each in its own language. Ersatz and folklore abound.”

Certainly stereotypical cultural portrayals should not be condoned, but in such cases as the above it might be gently pointed out that these pygmies and pirates exist within a blatant fantasy world. The ‘Jungle Cruise’ of the former is a tongue-in-cheek romp meant to be viewed as satire, and no one expects the dolls to come to life as true representatives of their countries (we hope). It’s all part of the Disney fantasy, and we are there to be swept up into the storybook.

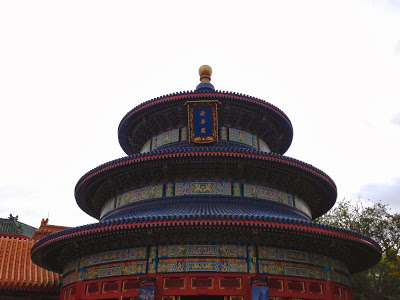

However, there is at least one park where this is not entirely accurate. One thinks of course of Epcot and its World Showcase, where twelve countries plus one African Outpost have pavilions, microcosms of faraway lands. It may be argued that Disney treats them as fantasies, but they are presented as real-life approximations, as if someone ripped out a chunk of Italy, of Mexico, of Morocco, and then plunked them down next to each other and called it a day. In direct contrast to this idea, Disney Imagineers created concept art for each country; this can only suggest nations were treated as concepts, not actual locales. Not that anyone at Disney would dare suggest such a thing. It’s like being there!

But we must know better. Once again, these pavilions are often a child’s first introduction to a particular country’s culture, but here they are taught to believe that what they are experiencing is genuine. Might we not say then that Epcot’s World Showcase is a multifaceted cultural ambassador for a new generation? If so, how is it doing, and why is it doing it?

To begin, it is important to understand how Epcot and its World Showcase came to be. It didn’t start as Epcot, for starters. At birth it was christened EPCOT Center, and the EPCOT stood for Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow; it wasn’t meant to be a theme park at all. Having made Disneyland a great success, Walt Disney (hereinafter referred to as ‘Walt’ so as to avoid confusion with the company and brand) really wasn’t terribly interested in recreating it in Florida, though by 1963 he was secretly buying up land to do just that. No, Walt’s new Magic Kingdom was a piggyback base for a much bigger project, a financial big brother for an idyllic community that exemplified the “EPCOT will always be a showcase to the world of the ingenuity and imagination of American free enterprise” (as shown in the famous Epcot teaser video). Walt’s heart was now in EPCOT center.

“We will never cease to be a living blueprint of the future,” said Walt in his promotional film for the project, “where people actually live a life they can’t find anywhere else in the world. Everything in EPCOT will be dedicated to the happiness of the people who will live, work, and play here, and those who come here from all around the world to visit our living showcase.” To Walt, EPCOT was a sort of American cultural ambassador in its own right, a means of showing off everything of which American industry was capable. Though he made mention in the film of sharing EPCOT’s advances with foreign visitors, his constant iteration of American industries, American technology, American imagination make it clear that he did not view it as a collaborative effort. One must not forget Walt’s distrustful nature after the labor strikes his studio suffered, or his consequent testimonials against “Commies.”

Unfortunately for EPCOT and, well, for Walt, Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966, before his promotional video was even released. Nevertheless, even without its father and main proponent, the film was presented to the public, followed by Walt’s brother Roy maintaining that plans would go forth provided that they had a “solid legal foundation” and the help of the locals.

Of course, we all know that ultimately the parks were in fact built, if not entirely how Walt envisioned them. The important information lies in how they were ultimately created, and for what reasons. Walt was certainly an innovator in many ways; the thing is, his genius lay less in art and creation itself and more in his drive, passion, and determination that those who worked for him created the best possible work to match his creative vision:

[Some studio employees] cited Walt as an inspiration, setting standards, expecting perfection, drumming up enthusiasm, buoying spirits. “I think the outstanding thing about Walt,” Jaxon said, was his ability to make people feel that what he wanted done was a terribly important thing to get done.” Another called Walt’s “greatest gift” his knack for “making you come up with things you didn’t know were in you and that you’d have sworn you couldn’t possibly do.” Walt was also a great cheerleader, exhorting his employees to think boldly. “I don’t want just another picture,” he would tell them. “It’s got to be a new experience, a new theatrical experience.” When he was enthused, as he usually was, he got others enthused too. “He was very excited about everything he was doing,” John Hench observed, citing a quality Walt had had even as a boy. “And he lived and breathed it and it finally rubbed off on you” (from Neal Gabler’s Disney biography).

And so with Walt dead, the company found itself, in the truest possible sense a metaphor could ever achieve, without its soul. It was Walt who had always had the image of EPCOT before him; his brother Roy and the rest of the team had been charged with making it all appear before him. The easiest thing to do would no doubt be to pull the EPCOT plan altogether, but so much promotion had been done already that this would be a serious loss of face; indeed, those within the company who did want to forget it found it impossible when the public continually made inquiries. Further, it had become a matter of honor. They had to do Walt proud.

The guiding mantra so often invoked by underlings before—what would Walt do?—became something of a curse. “The powers that be grew so afraid of doing something that Walt wouldn’t, that it resigned itself, in animation, live actions, television, and them parks, to repeat what it had done before” (from David Koenig’s Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation and Theme Parks). The paralysis spread through all facets of the company and landed square in the theme park projects, with the result that EPCOT morphed from an Community of Tomorrow to a Theme Park Similar to Yesterday’s, or as David Koenig so cleverly put it, EPTPOT: Experimental Prototype Theme Park of Tomorrow.

Similar to, but not exactly like. The company latched on to what bits of Walt original vision they could: “In attractive park-like settings, the six million people who visit Disney World each year will look behind the scenes at experimental prototype plants, research and development laboratories, and computer centers for major corporations.” Okay, so, they could create a park with a Future World, containing rides and exhibits themed to trends and advances in science, technology, and the like. This half of the park has a fascinating history of its own, but is not what we are chiefly concerned with.

Instead, we turn our attentions to the World Showcase, a brilliant funding plan if ever there was one. After all, why pay for your theme park when you can get other countries to do it? Gone were the days where Walt was “confident we can create right here in Disney World a showcase to the world of the American free enterprise system.” Instead, it was time to show America what the rest of the world was up to, at least that which they were willing to share. The company watchword was that Walt’s initial concept was “truly international in scope” and that, to quote Koenig’s Realityland, “like at a world’s fair, participating nations would give visitors a taste of their native lands and show off products and culture.”

In the infant stages, the World Showcase was intended as a stand-alone attraction separate from Future World, with its own minor five-dollar admission. It was to be built in conjunction with an International Village for the foreigners who worked within the pavilions, thus at least partially fulfilling Walt’s original community dream. However, it was eventually determined that the two would join together in one park, as EPCOT Center. In a fairly obvious correlation, the planned pavilions became that much more “themed,” with more emphasis on rides and attractions as opposed to the World’s Fair model that served as an inspiration. Again from Realityland: “The plans struck a comfortable balance between Disney-style attractions [executive Card Walker] was comfortable with and futuristic-sounding elements the public might associate with an Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow.”

The first cultural issue came in the selection of those countries represented. The Disney company had become well practiced in hooking sponsors for their creations. Over fifty countries were courted, with individual presentations for each, including mock layouts and concept art. However, it proved a harder sell than the company anticipated, with multitudes of countries committing and then pulling out. Nevertheless, deals were eventually brokered with private companies within each involved country, and the following pavilions were open when EPCOT debuted on October 1, 1982 (in order around the lagoon): Mexico, China, Germany, Italy, the American Adventure, Japan, France, the United Kingdom, and Canada, with a tiny African Outpost stop; a few years later Morocco was added and then finally Norway, in 1988. Although persistent rumors abound regarding new pavilions, none have been added since then.

Here ends our history lesson. Now it is time to see what observation and field research can tell us. Extensive time spent in the World Showcase yields interesting ideas about how culture is being represented within the World.

Much of it relates to children, as they are as aforementioned the most likely to be encountering these cultures for the first time; further, they are the more likely to have trouble separating the fact from the cleaned-up fantasy. Epcot has long suffered at the hands of children, at least by proxy; early on billed as an “educational” experience, parents veered away, thinking their offspring would be bored when comparing “The World of Motion” to “it’s a small world.” This idea was not helped by the early absence of Disney characters (Mickey, Donald, etc.) within the park.

But the Magic Kingdom’s redheaded stepchild was unwilling to accept this fate, and so a campaign was brought about to make Epcot more child-friendly. Among the attempted kid-lures is a Kim Possible interactive attraction [now defunct], but more apropos to the art world are Kidcot Fun Stop stations, set up primarily in each country for kids to engage in small art projects. Often simple white masks on popsicle sticks, they are decorated to a theme associated with a given country, although occasionally other crafts or activities do pop up. So score one for the visual arts, anyway.

But Kidcot is there as a means to keep children entertained, not to ensure that children absorb proper information about a given culture. So what are they absorbing? Never mind the children; what is any old visitor absorbing? Why, whatever is being put forth in the pavilion, of course. Let’s break it down into positives and negatives, shall we?

Leading off with the positives: all of the above skepticism aside, the World Showcase does bring other cultures to the forefront of peoples’ minds. This is perhaps less impressive when it comes to your more commonly considered countries like Germany and France, but how often might your average Joe ponder the wonders of Morocco or Norway otherwise? And sure, people are all up in arms about Mexico and immigration and what have you, but in the World Showcase they are so much more likely to simply admire the beautiful Mayan pyramid and clap along to the mariachi band. Maybe its not the most profound means of considering a culture, but with so much contention between nations, let us not forget the power of positive relations.

Speaking of which, the Disney International program brings foreign workers into the country legally and without fuss. Great for the Mexicans of course, but this also assists America with its constant, desperate need for other countries to just please like us. Heck, Disney has the French volunteering to come live and work here. Hopefully the impressions of America these workers take back to their countries of origin are, again, positive.

Then there is the sampling of arts and artisans that the World Showcase provides. Both permanent and rotating exhibits and performers are nestled in the pavilions. In Japan there is a museum exhibit of tin toys, and Miyuki, a candy artist; in Mexico, Los Animales Fantasticos, painted wooden animal spirits [I think this is defunct?]. Norway’s beautiful church showcases the architecture of the Vikings, and Canada’s indigenous totem poles offer a fascinating view into both art and history. There are both French and Italian mime styles and Chinese acrobatics. During the holiday season, there is a native storyteller in every pavilion, such as China’s Monkey King and France’s Pere Noel. Add to this fusion music by Mo’Rockin’ and Off Kilter, then the more traditional sounds of China, and the UK’S British Invasion, and you have a veritable smorgasbord of local culture, assuming you are local to a lot of places.

Similarly, you have a wide variety of foods and, ahem, alcoholic beverages to try. There are of course restaurants offering the national cuisine in every pavilion, but Epcot will do you one better. The annual Food and Wine Festival features vestibules for every country in addition to at least a dozen more in between, all offering taste treats in sample sizes. Visitors can snack their way around the world in one meal.

All of this is good. Now for the bad! Starting with food, since we just discussed it. Epcot’s restaurants suffer from what you might call the “Chinese Food Effect.” That is to say, what your average American Chinese restaurant anywhere in the country offers is generally considered by native Chinese to be about on par with what’s served in the school cafeteria. The same goes for the vast majority of the World Showcase’s kitchens. You’ll likely enjoy the food and it’s not unauthentic, but it’s not exactly the finest example of cuisine, either. Further, the overarching food management pulls such tricks as serving the exact same plum wine in Japan as they do in China, which is to suggest that all plum wine as the same, which is akin to saying that all beer is the same, and we understand this to be incorrect.

The overall feel of a World Showcase pavilion is that of absolutely accuracy if the country was looking its cleanest and prettiest, yet somehow this does not extend to the costumes. While the architecture outside is a pretty facsimile, the uniforms are barely even that. Polyester and for the most part straight up ugly, this seeming nitpick is actually a great detriment to the experience. Fashion is considered an art, but even beyond that, traditional costumes are often a practical flashpoint of culture, representative of both practicality in daily life and a culture’s concept of what is lovely, what is to be highlighted on the body. That Disney chooses to disregard this importance is a disservice indeed.

One must also factor the matter of the current economy into the equation. Though Disney has made claims that park attendance has in fact increased over the past year, budget cutbacks tell another story; indeed, the entirety of the Downtown Disney club complex Pleasure Island was shut down in September of 2008. Yet Disney is as tragically injudicious with the knife as the rest of society, slicing out the arts before it goes elsewhere. African drumming group Tam Tam used to perform in the African Outpost, but now the only sign of their former glory is a few lonely prop drums by the Coke machines. Disney even staggers opening times for World Showcase to cut down on employees, with opening and closing times often two hours before or after Epcot proper opens and closes.

And then, inevitably, there is plain narrow-mindedness. Disney is very strict about its appearances. “I went to Germany to look for German musicians,” says Bloustein via Koenig, “and they were the pits. They were the worst musicians. There was no such thing as a young musicians in Germany. They were a bunch of old farts sitting in biergartens. And they only played for fifteen marks—twenty marks if you wanted to conduct them. It was just terrible.”

Ultimately he brought in a group from Hamburg, New York. He told the musicians: “’Now, if you can, for the first six or seven months you must always say you’re from Hamburg. And try to put on a perfect German accent. You know, [as if] you’ve only been in the States for six, seven years.’ As far as the company knew, the musicians came from Hamburg. I never said Hamburg, Germany. I never said Hamburg, anywhere.”

Similar stories abound:

In Italy, Bloustein wanted an improvisational commedia dell’arte group. Several months before opening, he recruited an authentic repertory company, completely with period costumes and masks, and gave them a trial run at the Lake Buena Vista Village shopping center. Passerby would stop for a moment and then continue walking. In the meantime, while attending a Renaissance faire, Bloustein discovered a trio of irreverent street performers called SAK Theater. “I brought up these three people from Minneapolis, and they were hilarious,” Bloustein recalled. “Within five minutes they had 150 people standing there—and sitting on the ground, and doing all sorts of terrible things. They just knew how to deal with a crowd. So I hired them and put them in Italy.” (from David Koenig’s Realityland)

Authentic!

Let it not be surmised that Disney is at fault entirely for all that is bland, generic, and spit-shined for our cultural consumption. With the exception of Norway, all pavilions in the World Showcase are sponsored by private companies. As such, they have the option to pull their money, and hold some power over Disney even as Disney flashes their important brand name. Part of it is inherently a brilliant tourism ploy, for what better opportunity could you ever find? They reel in customers daily with their food and their merchandise and their pretty portraits of the ideal wine-filled life for the taking if you come to France, or the oceans of cheddar cheese soup that can be yours in the rustic wilds of Canada. As promotional materials go, you’ll scarcely see better. If a private company was displeased with the cultural portrait being painted, they could pull their money, or threaten to do so if a more accurate picture was not produced with haste. Yet the World Showcase has stood for twenty-five years unchallenged.

|

| I found this carved on the inside of a bathroom door. |

But Disney is very proud of its compressed globe. They delight in creating a fantasy out of cold reality. “The authentic avenues in the Morocco pavilion,” the Imagineers boast through Eisner’s Imagineering book, “appear as though they have been in existence for centuries. Guests often comment that once they step away from the World Showcase Promenade and disappear into the backstreets of Morocco, they feel as though they are not in Epcot at all.”

One the one hand, we should fight against this mentally, that we wish our worldview to be washed and pressed before we touch it. But on the other… where’s the harm? Why should we not admire other cultures through the forgiving pink tint of rose-colored glasses? We vote with our dollars every time we pay for a ticket and walk through the gates of Epcot.

Eventually, Walt got his EPCOT, or at least an approximation on a very small scale, in Celebration, a fomerly Disney-run community just outside the property. But while it is in fact Disney operated and created with an idyllic and forward-looking existence in mind, it pales in comparison to Walt’s brainchild. Yet even if EPCOT-cum-Epcot is not precisely what Walt would have wanted, it is what he got, and many would cite it as their favorite among the parks. Part of that is no doubt due to the fact that you can in the course of an evening stroll through a dozen countries and sample their culture. Even if it is not the most accurate portrayal, it nonetheless requires that, for a few moments and through a haze of authentic local beer, we contemplate the country that brought us here. Contemplating must be the start of understanding. Inspiring understanding—could one not argue that was what Walt wanted all along?

There is so much more of Disney’s parks and culture, be it as regards the American parks and their cultural lens or how Disney merges with the locals in its parks in Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Paris. The World Showcase is but the tip of the proverbial iceberg, albeit a particularly juicy one. Like Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged, we will never be done. At least, not until tomorrow.

Don’t forget, you can follow FRoA on Twitter @fairestrunofall and on Instagram @fairestrunofall. If you have any questions or thoughts, leave a comment or email fairestrunofall@gmail.com. See ya real soon!

No, we really are the same person. As a nerdy kid, I was in 8th or 9th grade and I loved going to the Japan pavilion and I literally hung around speaking Japanese with the people who worked there, so in that sense it was educational.

At Food & Wine this year and there is now a kiosk just called "Africa" (which I'm assuming replaced South Africa) in that bogus pavilion that don't even get me started. Uuuugh, Disney, why do you have to be so problematic for me. The "Africa" section of It's a Small World is basically 75% animals as opposed to actual humans and there was a youtube video of Walt narrating the ride at the '64 world's fair where he called it the "dark continent" and it was just one of those moments where I'm all, "I WANT TO LOVE YOU BUT YOU'RE MAKING IT REALLY HARD." I don't know how much Animal Kingdom really changes the underlying problems I have with the way Disney represents Africa, if only because it's again about the animals as opposed to actual people and I can't help but feel like it just reinforces a very problematic message re: race.

Another good one to read is Vinyl Leaves, a sociologist who opens his book with "I got tenure, so I'm going to Disney World!" It's really interesting and my personal favorite: the Architecture of Reassurance.

Yeeeah… poor Africa has never really gotten a footing. Well, actually, strike that – Africa the continent has a GREAT footing, but for some reason only Morocco has managed to be individually recognized. I really wish Epcot would add, I don't know, Kenya or Nigeria or something.

I was impressed, though, with a lot of the opportunities for cultural interaction at the Animal Kingdom Lodge. There are tons of people from different African countries there, with daily learning activities. More of that, please!

I have only been once, but I never thought of it like that. Great perspective.

Thanks! You should definitely go back; it's a great park.

You should definitely go back; it's a great park.